3.1 Initial Stage

Weathering is the chemical alteration caused by the atmospheric water in vapor and/or liquid form, due to the reacting agents carried in solution. Thus, this was the first step in the alteration of the original consolidated rocks forming the initial land masses. Figure 29 shows how the most reactive minerals are preferentially affected.

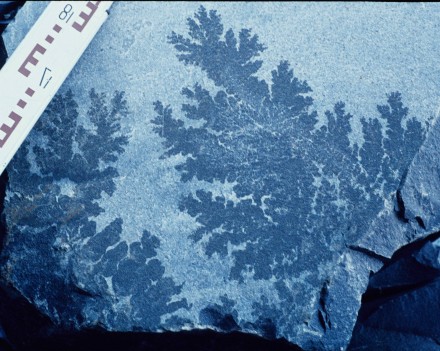

Also, the less soluble materials of the weathered rock will precipitate in the immediate vicinity, along fissures and/or bedding planes through which the water percolates. For example, the manganese dendritic growths frequently found on bedding planes and joints (fig. 30).

Figure 30 – Manganese dendritic growths on a quartzite bedding plane (Peninsula Quarry, Cape Peninsula, South Africa).

These differential weathering characteristic can also be noticed in the variability between two different members of a rock outcrop, such as in figure 30B. In fact in this example one can see a progression of the weather-erosion (item 4) sequence. Behind the photographer there is fresh dolerite indistinguishable from the limestone across which the dyke cuts. This is followed by the pale brown section of very weathered dolerite already forming a trough along which rain water will converge accelerating the weathering as well as transporting that weathered materials in to the sea, by which section the dyke has been completely removed, thus forming a very sharp topographical contrast.

Figure 30B – Totally weathered and partially washed away dolerite dyke cutting through a limestone succession (Cabo Raso, Cascais, Portugal)

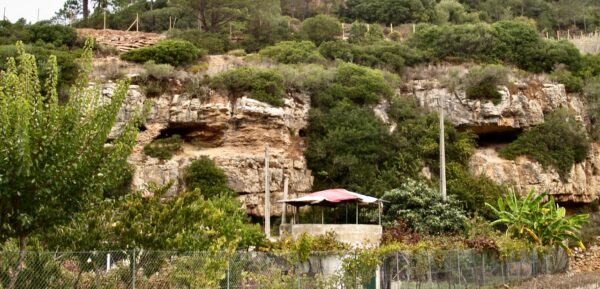

Of course, although not as noticeable, this contrast is also present within a horizontally laying succession, as exemplified in figure 31, where a more easily weathered bed of bioturbated limestone is sandwiched between two much more resistant layers, giving rise to the formation of caves.

Figure 31 – Easily weathered bioturbated limestone with caves, sandwiched between more resistant limestones beds (Estoril, Portugal).

3.2 Soil Formation

The above examples are rather exceptional, because more often we have reasonably flat areas with uniform rock outcrops where the weathering is widespread, giving rise to the development of soils. In this respect it is interesting to identify an ancient soil (palaeosol) preserved within a stratigraphic sequence.

3.2.1 Laterite

A very good example of a palaeosol is shown in figure 31B where on the right hand side, the lowermost member of the succession has a blotchy wine colour, corresponding to a completely weathered basalt layer. That is, this is an ancient soil, which is covered by a layer of very angular rock fragments and above that we have a layer of almost unaltered lava. I present this example first because it shows very well how a soil horizon can be preserved within the rock column. More, the blotching indicates a mineral assemblage with different chemical compositions, and if this weathered material had been transported, the blotches would have disappeared due to the mixing. Thus, we have an “in situ” palaeosol.

Figure 31B – Basic lava weathered to soil overlain by a layer of hill slope debris, covered by moderately fresh lava (Tagus estuary, Oeiras, Portugal)

The weathering caused an enrichment in iron, giving rise to a laterite, and if this laterization had been more intense, the iron concentration could have been considerably higher (figs. 31C and D). Note that if the original rock had been rich in aluminium, bauxite would have formed.

Figure 31C – Laterite field, rather barren compared to the lush vegetation in the background (Orissa, India).

3.3 Special Aspects of Weathering

3.3.1 Gnammas

The difference in reactability of the various minerals constituting a rock gives rise to interesting surface features. One such case is the formation of cup shaped holes on granite outcrops at mountain tops, known as gnammas (fig. 31E). I presume these remarkably circular depressions are caused by the weathering of the feldspars and other chemically unstable minerals into clays, initially in single rain drops size cups. This because in winter, the snow or the freezing rain drops will fragment the mineral lattice, which will then become much more susceptible to weathering when the water melts. With the continuation of this cycle, the clay formed by the weathered minerals, being very light, is washed away, enlarging the cup and exposing additional surfaces of fresh rock. In the mean time, the much more weather resistant quartz grains present get loosened and acumulate at the bottom of the cup as shown in the picture.

Figure 31E – Granite weathering in the form of very circular cups (gnammas) (see keys for scale) (Serra de Freita, Arouca, Portugal)

When the rain is stronger, these quartz grains will also be washed away, thus allowing the continuation of the enlargement of the cup, which can eventually reach significant dimensions like the ones at Marinieche in France, as was shown to me by Jean Jacques Espirat, another geologist. In fact, after his communication, I changed my mind about a depression in a granite boulder, with a mouth diameter close to 2 meters, which I photographed at the margin of the Orange River in the Agrabis Falls area, in South Africa (fig. 31F).

Figure 31F – A very large gnamma (approximate diametre 2 m) (Agrabis Falls, Orange River. South Africa).

I had originally interpreted it as being a river pothole, at a site which, although with an elevation somewhat higher than the present river bed, I presumed it was where the river previously flowed. Perhaps another point in favour of this new interpretation is the fact that river potholes tend to be deep and have a proportionally narrow mouth, as against these weathering cups which appear to be shallow and have a relatively large mouth.

3.3.2 Jointing

3.3.2.1 General

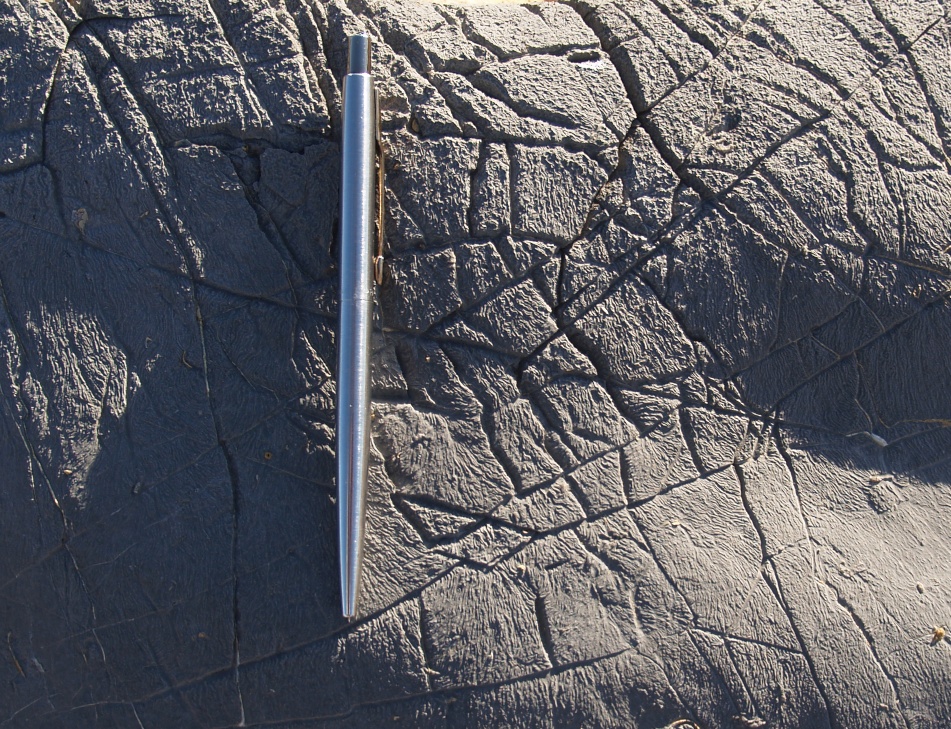

The larger the surface area being affected by the weathering, the more effective it will be. That is, the more cracked the original rock, the sooner it will become weathered, since the cracks greatly increase the area exposed. Cracks develop, for example, due to the influence of the temperature variations from night to day, causing consecutive expansions and contractions. Along these cracks the weathering will have a larger surface of impact and it will often form troughs. This is well demonstrated in figure 31G where the weathering effect on a gray limestone has such a similarity to the skin of an elephant, even the colour, that in South Africa this type of weathering is known as “elephant’s hide weathering”.

Much better defined cracks (joints) develop when buried rocks are released from their surrounding pressure. Mining for example, when the ore and associated waste is extracted, relieves the surrounding rock body from its original tension. Figure 31H shows the cracks developed by the pressure release caused by the mining of this dunite pipe. Further, the humidity that concentrated along these cracks, accelerated the weathering, causing the alteration of the dunite into magnesite, which now frames the joints so distinctly.

Figure 31H – Magnesite after dunite, developed along the pressure release joints around the pipe mined for platinum (Bushveld Igneous Complex, South Africa).

3.3.2.2 Box-Work

It also often happens that the joints could have been previously filled with a more resistant material, in which case they will tend to form ridges (fig 32),

giving rise to a surface texture with the obvious name of box-work, which comes in all sizes and is quite noticeable in limonite rich sediments (fig. 33).

Another example is the spectacular weathering sequence initiated with the alteration of olivine to serpentine (fig. 34).

Figure 34 – Serpentine after olivine, notice the initial formation of a box-work texture (view approximately 100 x70 cm) (Orissa, Boula, india).

This is followed by a marked increase in the box-work texture, and the alteration of serpentine to breunerite (fig. 35).

Figure 35 – Breunerite after serpentine with a distinct box-work texture (view approximately 100 x70 cm) (Orissa, Boula, India).

3.3.2.3 Exfoliation

On a much grander scale, are the joints formed during the uplifting of rock masses caused by isostatic adjustment. A good example is seen in granite outcrops. Granite is formed at great depths and thus at very high pressures. Erosion will eventually bring these large igneous rock masses to the surface reducing dramatically the surrounding pressure and causing them to break into large blocks. Since the weathering will be most intense at the block corners, these, with time tend to become rounded and the decomposition more concentric, causing a pealing effect like an onion (exfoliation). This is well illustrated in figure 36. where one can see examples ranging from blocks with barely rounded edges, to blocks that are almost spherical and blocks where the exfoliation is quite distinct.

On a granitic land surface, this can be seen in a grand scale, because it gives rise to the very characteristic geomorphology of upstanding huge egg shaped solid masses, known as inselbergs (fig. 37).

But, on the granitic land surface shown in figure 38, a very unusual effect of the decompression and enhancement of the exfoliation by weathering is apparent. The boulders resemble piles of pancakes. Most likely this lamination effect was caused by prior strong shear pressures on the granite mass.

Figure 38 – Unusual exfoliation in granite (granite pile approximately 1 m high) (Serra de Montesinho -Trás-os-Montes. Portugal).

3.3.3 Sink Holes

Perhaps the most devastating weathering effect is the one giving rise to sink holes. Acidic waters dissolve limestones and dolomites very easily, and the contrast with other interbedded sediments is very distinctly seen in figure 38B where the highly soluble dolomite in the upper portion is full of hollows, as against the totally insoluble chert horizon below.

Figure 38B – Highly weathered limestone horizon (above), and unweathered chert band below (Sterkfontein Caves,Transvaal, South Africa).

The consequence of this limestone solubility on outcrops gives rise to a very irregular surface with rather deep hollows, termed “karst” (fig. 39).

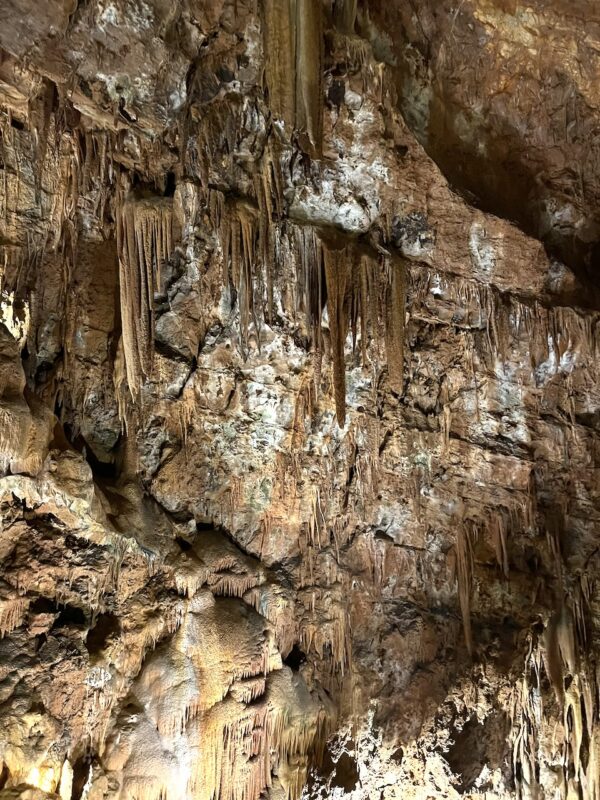

This weathering action continues under the surface anywhere above the ground water table (vadose zone). Thus, where the water table is sufficiently deep, the limestone will continue dissolving above, and caves will develop with time. Later, that water will become saturated with calcium carbonate, and precipitate, forming stalactites (fig. 40),

Figure 40 – Formation of stalactites due to the precipitation of the calcium carbonate from the saturated dripping water (Mira de Aire, Portugal).

which will concentrate along bedding planes and joints through which the underground water will preferably percolate (Fig. 40B).

Figure 41 – Concentration of stalactites along the bedding planes and joints (Mira de Aire caves, Portugal).

By the way, I think these caves at Mira de Aires are geologically rather young because the stalactites are still rather small, and the stalagmites are practically non-existent (fig. 41).

Continuing, if the conditions remain constant for long periods, the weathering of the limestone will progress, causing the dimensions of the caves to increase, reaching a stage when the ceilings, generally in the form of a vault, will no longer support the mass of ground above, and will collapse, forming sink holes. Even small sink holes can cause significant damage like the one shown under the railway line in figure 42.

On the other hand, particularly interesting is the double sink hole shown in figure 43, where initially the dome collapsed, but somehow its central sector maintained its shape, to eventually subside at a later stage.

Figure 43 – Reactivated large sink hole (for scale, the parallel marks on the right hand side, are motor car tracks) (Carletonville, S. Africa).

In the mining town of Carletonville, South Africa, the Witwatersrand Group with its famous very rich gold horizons is overlain by a very thick dolomite succession. In 1978 when I worked there, there were 4 deep gold mines which pumped to the surface in excess of one million cubic meters of water per day, in order to maintain the underground workings sufficiently dry to enable the mining operations. As a consequence, the ground water table (phreatic level) dropped tremendously, in some places to more than 500m below surface, causing the development of large areas with perfect conditions for the formation of caves which naturally progressed into numerous sink holes. This eventually caused the evacuation of a few of the mining villages, because of the collapse of some of the constructions and the unfortunate death of some of the inhabitants.

Much more frightening though, is what occurs in Slovenia where the village of Skocjanske (fig. 44),

Figure 44 – the village of Skocjanske suspended amongst limestone arches separating different sink holes (Slovenia).

is located on top of arch remnants separating old sink holes (fig. 45). Having lived in Carletonville, I do not understand how a village can continue being inhabited under such conditions.

Wow! Thank you!

I always wanted to write in my site something like that. Can I take part of your post to my blog?

Of course, I will add backlink?

Sincerely, Reader

I’m glad it is of use to you, sure you are welcome to make use of what suits you. Naturally this is a work in progress so any positive comments will be appreciated.

All the best

hi, I am a geologist at Columbia University in New York. I am quite interested in the rates and processes of mineral carbonation, particularly formation of carbonates by reaction of CO2-bearing fluids with olivine and serpentine. I came across your image of magnesite veins forming in a dunite pipe in the Bushveld complex.

Some questions:

(1) May I use your photo in a paper to be submitted, perhaps to the journal “Geofluids”? If so, how shall I reference the source of the photo?

(2) Are you sure that the magnesite veins formed after the mining, and not before? Do you have before and after pictures? It would be really great to have a rate estimate based on before and after photos.

Hi,

You are most welcome to use the photo the way it suits you best. As for your questions, I took this photo in 1970 and if my memory does not fail me, the pipe was mined in the early 1940s and our professor took us there specifically to show us the weathering effects after mining.

I wanted to know about the iron boxwork feature which I saw very-well developed in Barmer area, Rajasthan, India. These are text-book like features developed on calcareous horizon.

Thanks for details.