8.1 GRASS ROOTS

Grass roots exploration is the general term for the very initial stage of prospecting that starts from a zero base, that is, neither geological maps, nor aerial photos are available, and often not even topographic maps. Of these, my first experience was in Mozambique in 1972, when communication with the outside world was a very precarious land line and some times, when we were lucky, a fax, both by means of the post office at the nearest village, which was about 150 km away. I do not think it appropriate here, to go into the prospecting work itself which consists of mapping, sampling, drilling, data interpretation and a final data synthesising. However, under advanced prospecting I will show some photos referring to sampling which, I think, takes most of the geological time.

8.1.1 Transport

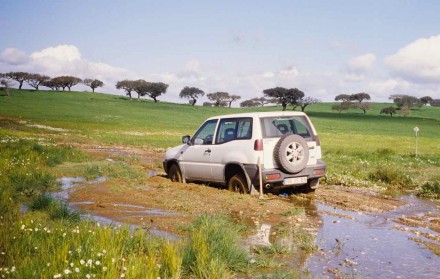

In areas of grass roots exploration, most of the times even the main roads are simple tracks across the veld. Hence a tough reliable 4 wheel drive vehicle is fundamental as this example, still in Mozambique and which was my baptism of bundu bashing, indicates. Figure 143 shows the end of my successful attempt of taking my lovely car out of a river side mud bog. I was alone, and it took me 4 hours to get it out.

Just for comparison purposes I also show the same kind of experience, but in Portugal in 1996 (fig. 144). This time it was easy, we only had to call the local farmer to bring his tractor and pull us out. So, not only was this in a different continent, but also 24 years later.

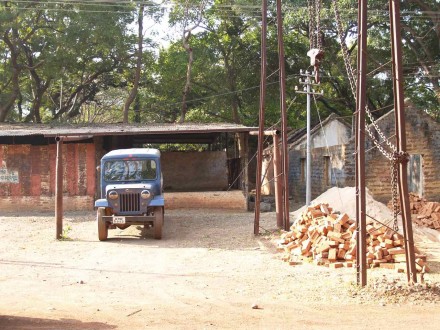

What I want to make clear is that if I had the fancy comfortable white car in Africa, even today, it would take me perhaps weeks to get it out, if at all. This because today’s sophisticated jeeps have so many complicated electronic gismos that one needs to have a highly qualified, not just mechanic, but a well equipped garage within easy reach. Unfortunately I’m now considered too old by the powers that be, to continue prospecting. One thing is sure though, if I did go, the jeep I would choose is the Indian manufactured Mahindra (fig. 145). It is incredibly robust and has a totally old fashioned simple, reliable engine that will go anywhere and the only assistance it needs is regular greasing and any simple mechanic assistant to deal with minor difficulties. Just as an interesting memory of my stay in India, notice the jeep’s front decorations with the string of flowers and the painted swastikas. This is a must to make sure the car is accepted by the gods.

8.1.2 Accommodations

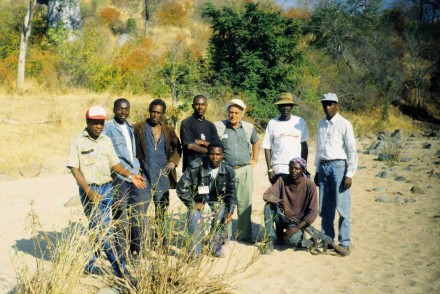

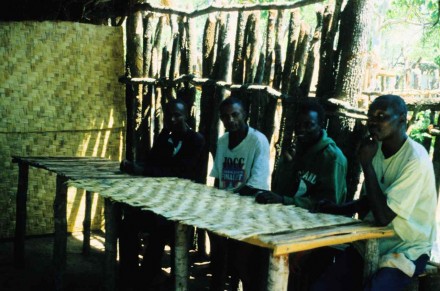

Even in many remote parts of Africa it is often possible to organise a side farm building or similar locations to use as living and working quarters. When that is not possible, as in my stay in Angola, one has to organize camping facilities which must have a minimum of practicality and comfort. My full staff (fig. 146) consisted of one local geologist, one local person of the correct tribe and political affiliations, one overall organizer, two security guards (hence the guns), one cook with an assistant and two laborers. I was fortunate to find a very reliable and professional organizer, Vete Willy, who not only built our camp but also kept it going, always in impeccable conditions. He is not in the picture because, other than me, he was the only one capable of using the straight forward Zeiss Ikarex camera I had.

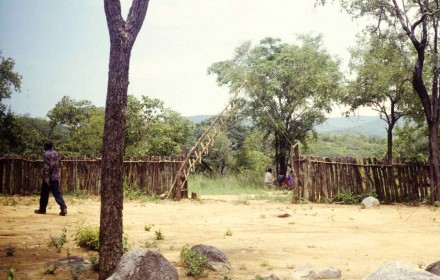

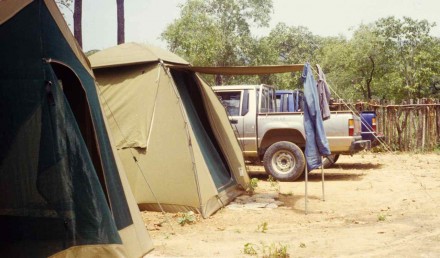

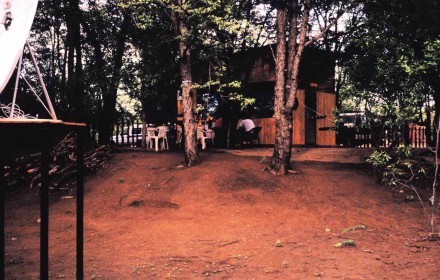

I was working for a medium sized mining company but, not so far away, there was the camp of a very large mining group, who also had to arrange a camp and whose chief geologist I became acquainted with. Since I have pictures of both camps it is interesting to put them side by side. The dimension difference is impressive. Two of my whole camps (fig. 147)

would fit within the entrance area of the other camp (fig. 148). Or putting it another way, when there are funds, much more can be done in a much shorter period, and in much more efficient working conditions.

Figure 148 – Large mining group entrance to their camping site and chief geologist’s caravan (Caama region, Angola)

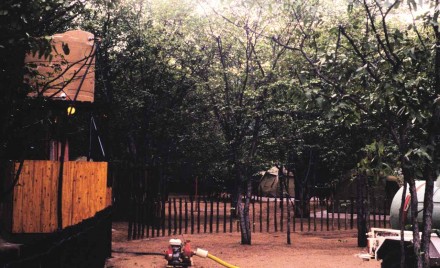

The fleet difference is also striking. Figure 149 shows my two cars,

and figure 150 shows part of the, let us call opposition, fleet. Also shown in my camp is my tent in the foreground and the office tent in the middle ground. Naturally this little office was strictly for rough work. We did have a comfortable house and office at the nearest town.

Going now to the eating facilities, the comparison continues to be striking. Not only is there a great difference in space, but also the accommodation and the furniture. My little dining hut (fig. 151) was built with the minimum of the essentials.

The other one even had a TV, with its dish aerial at the left edge of figure 152 . One must be fair though, I did have a satellite phone and it worked pretty well. It was not as bad as in Mozambique but, after all, I was in Angola in 1997/8, that is, 26 years later.

Finally, the ablution facilities. Our toilet (fig. 153) was the long drop method and to reduce unpleasant smells it was sufficiently far away, outside the camp area and on the correct side of the prevaling winds.

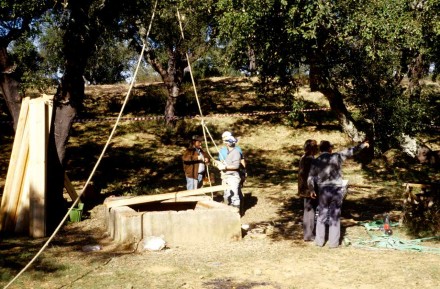

Notice that the opposition even had a water pump so that one could have a nice cleansing shower at the end of the day (fig. 154). In my case, to wash we had to go to the nearby river and use the remaining water pools during the dry season. I will never forget though, the most enjoyable showers I had. During the rainy season it practically rained every day, and often late in the afternoon, that is, at the correct time to clean all the work day dirt and sweat. I would undress in my tent, come out with the soap and use the rain as a shower. It was divinely refreshing and it lasted long enough for me to complete the job. It is definitely a lovely memory.

8.2 ADVANCED PROSPECTING

8.2.1 In the Field

After basic geological mapping, trenching is often used, especially over areas with poor or no outcrop. Additional geological mapping is done along them and, when applicable, tentative initial trench sampling will also be considered (fig. 155).

Nowadays, after detailed mapping as well as soil, trench and rock outcrop sampling, if the indications are positive a drilling programme will be planned. In the old days short underground adits into the hill sides would be cut or, in flatter areas they would sink small shafts from which adits would be cut, generally along strike. In present day prospecting sites it is frequent to encounter such old workings. Since geologists are eternal optimists, the assumption is that whoever was there before did not prospect well enough or, most likely, the price of the resource concerned was not high enough to make the venture viable at that stage. Obviously, these old workings are always very closely scrutinized since they will add valuable data at practically no additional cost (fig 156).

Returning to the rock outcrop sampling, it is most advantageous where the outcrop is good and continuos, since it is much cheaper than drilling. In the old days the sampling was done by chipping the rock with a hammer and chisel, but now there are diamond circular saws that do not need water to cool. It makes the exercise much simpler and faster, although a bit dusty, hence the masks (fig. 157).

Figure 158 shows the sample groove and respective number.

At this stage, if all indications are positive, a drilling programme is planned and budgeted. It is now fundamental to prepare a yard (fig. 159) to store the drilling core and also a sample preparation laboratory where the samples can be cut, crushed, quartered, a portion sent to an assaying laboratory and the remainder kept for potential future use. Naturally this sample laboratory must have all the necessary equipment to prevent contamination. For the more basic prospecting facilities the core is simply split and half is sent for assaying.

Figure 159 – Initial stage of preparation of future core shed, left, and sample preparation lab, right (Boula, India).

Drilling especially in new areas, is done not only for sampling purposes, but primarily to assist with the identification and interpretation of the rock assemblage where the ore is located. For that, not only must each hole be meticulously geologically logged, but more important still, the core of as many of the holes as possible, must be laid side by side to facilitate in the identification and correlation of the constituents present, in order to determine the local stratigraphy, hence the need for a large yard. Figure 160 is the core yard where I was fortunate enough, at a very early period of my career, to be present during the initial stages of a diamond drilling programme in the Bushveld Igneous Complex and assist a very capable senior colleague. His good understanding of the stratigraphic principals lead to the identification of all the individual units immediately above and below the Marensky Reef (item 2.3 Magmatic Differentiation), so necessary for a successful final synthesis.

8.2.2 In the Mine

Prospecting is not done only to find new ore resources but, just as important, it is necessary when, for example, in an already working mine, there is the possibility of exploiting an additional ore which was previously considered uneconomical. In that case, the waste dumps of the original extraction, must be reevaluated to ascertain if there is enough of the second element to be re-qualified as ore. This is what happened at the chrome mines at Boula, India, where platinum was identified and it was hoped it might have sufficient grade to be exploited as well. The first step to ascertain this possibility was to sample the chromite waste dumps (fig. 161). The little markers seen all over the stone pile actually form a well delineated sampling grid. It is possible that the sampling method selected, which only used chips cut from every piece of rock within the delineated square might not be adequate, but that is how it was done. The next stage was to sample the chromite ore exposed on the open cast pit (fig. 157). This would be followed by a drilling programme for which the necessary core shed and sampling lab were already being prepared (fig. 159). At that stage I left the project.

Figure 161 – Chrome mine waste dump sampled for platinum (white tags on little metal rods) (Boula, India).

8.2.3 Sampling

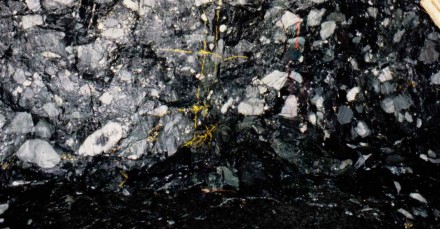

As already mentioned, sampling is a vital item of prospecting without which a factual synthesis is not possible. Thus, its correctness and reliability is fundamental. Even though figures 162 and 163 actually represent stope sampling for grade control in a mine, they are good examples to show the basic importance of strictly adhering to a statistically predetermined grid. The yellow lines are actually the markings of each sample. When I left the gold mines the hammer and chisel chipping method was still being used, hence the shape of the area to be sampled. Careful examination of figure 162 shows very nice looking buckshot pyrite just to the left of the sampling line. This means good gold values, because there was a direct relationship between buckshot and gold. Since there is no buckshot at the sample location, its gold value will most likely be poor. However, if the sampling position is moved to include the buckshot, we are no longer dealing with a sample but rather with a bias grab specimen.

In figure 163 we are dealing with an ore horizon consisting of various conglomerate bands separated by quartzite, termed internal waste because, as it should be expected, it never carried any gold. In the present case, for a detailed study and considering the abrupt changes in thickness of the conglomerates the sampling zone consists of four adjoining sections.

Figure 163 – Underground detailed sampling for gold in the Witwatersrand, South Africa.